You see a viral dance step tutorial video on TikTok, Instagram Reel, or YouTube Shorts and think yourself – I could do it easily as well. You see a plumber fix the leaking tap rotating the teflon seal tape over the tap thrice, and you think yourself – I could do it easily as well. You observe a workshop facilitator conduct a two hours session, and immediately think – I could do it easily as well. The list goes on.

You could do it easily. But chances are, you could struggle – and fail miserably. Many of us overestimate how much we can learn by observing others. I thought I could learn guitar chords just by watching people play over the YouTube videos. And boy was I wrong.

This is a common phenomenon in learning – the illusion of skill acquisition.

Easier Seen Than Done: The Research

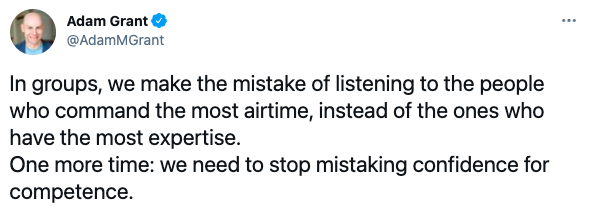

In a fascinating study at Northwestern University, researcher Michael Kardas had participants watch videos of skills like dart-throwing and the moonwalk dance multiple times, some even up to 20 times. After watching, they were asked to guess how well they could perform these skills before giving it a shot themselves. Surprisingly, many believed that just by watching the videos, they could become skillful. Interestingly, the more they watched, the more confident they felt about their abilities.

However, the study’s results were unexpected. Despite feeling more confident with each viewing, the participants didn’t actually improve in performing the skills when they tried them. Their confidence in learning through observation didn’t match the reality of their unchanged performance. This highlights the misconception that simply watching instructional videos can lead to skill mastery, emphasizing the importance of active practice and engagement for effective learning.

Can you land a plane?

Passive observation can have a surprising effect on people’s confidence in handling challenging tasks, even life-or-death situations like landing a plane, as discovered by Kayla Jordan, a PhD student at the University of Waikato, New Zealand. Inspired by Kardas’s research, she wanted to explore if this phenomenon could extend to highly skilled tasks. Piloting, for example, demands extensive training and knowledge of complex subjects like physics and engineering, far beyond what a short video can convey.

In their study, participants were asked to imagine being in a scenario where they were the only one left to land a plane due to the pilot being incapacitated. Half of them watched a brief video showing a pilot landing a plane, while the others did not. Interestingly, the video didn’t provide any instructional guidance on the pilot’s actions during the landing. Despite this, those who watched the video showed a significant increase in their confidence to successfully land a plane themselves, about 30% more than those who didn’t view the clip, as noted by Jordan. This highlights the intriguing way in which passive observation can influence one’s perception of their own capabilities in demanding situations.

Why does this happen?

If you have been around a child, you will know that they imitate their elder ones. Human beings – since their infant age – watch others and learn. This is the basic premise of the “Social Learning Theory”, developed by psychologist Albert Bandura, which explains how people learn new behaviors and skills by observing others.

This theory highlights three key aspects: observation, imitation, and modeling. First, you observe someone else’s actions. Then, you try to imitate what you saw. Finally, through practice and feedback, you model your behavior to become more like the observed behavior. Bandura also emphasized the role of reinforcement and punishment. If the person you observe gets praised for their actions, you’re more likely to copy them. Conversely, if they get punished, you’re less likely to follow in their footsteps.

However, in case of illusion of skill acquisition, we don’t really reach the imitation and modeling phase. We observe and then do not engage in deliberate practice. Without deliberate efforts made into practicing, we don’t get required feedback for corrections, which means we omit the modeling phase as well. Humans are social beings, and much of our learning occurs through observing others. Mirror neurons facilitate this type of learning, which can be efficient but also prone to creating illusions of mastery.

Here’s the culprit!

I was watching my mom cook a delicious meal. I noted everything she did – from the steps to the list of ingredients. A few weeks later, I replicated her every step. It was a disaster. I swear I did all the steps right, but I don’t know why the meal was a disaster! From childhood, I have learnt cooking from watching others cook – be it in my own kitchen or in the TV cooking shows. That has helped me gain knowledge about cooking new dishes. I have ideas about new dishes, recipes, and the ingredients used – but have I learnt how to cook it? Probably I can’t say unless I give it a try.

This sort of learning is facilitated by our mirror neurons, which is referred, rightly or wrongly, as “The most hyped concept in neuroscience”. Mirror neurons are a type of brain cell that responds both when we perform an action and when we observe someone else performing the same action. Mirror neurons are also said to be responsible for being more empathetic towards another person. They are thought to be involved in understanding others’ actions and intentions, as well as in learning through imitation.

While mirror neurons help us learn by observation, they can also create a false sense of competence because they simulate the action in our brains without actual physical practice or feedback.

So what to do now?

Overcoming the illusion of skill acquisition requires a mindful approach to learning and practice. Here are three actionable things you can initiate to overcome this illusion:

Engage in Active Practice: Instead of passively observing or assuming that watching others perform a skill will lead to mastery, actively engage in practice yourself. Practice involves hands-on experience, allowing you to develop muscle memory, refine techniques, and gain a deeper understanding of the skill. By consistently practicing and actively applying what you’ve learned, you can bridge the gap between understanding a skill conceptually and being able to execute it effectively.

Seek Constructive Feedback: Feedback is crucial for skill development as it provides valuable insights into areas of improvement and helps you correct mistakes. Actively seek feedback from mentors, instructors, or peers who are experienced in the skill you’re trying to acquire. Constructive feedback not only highlights your strengths but also pinpoints areas where you can enhance your performance. Embrace feedback as a tool for growth and use it to adjust your practice strategies and refine your skills effectively.

Set Specific Goals and Track Progress: Establish clear, measurable goals for your skill development journey. Break down the skill into smaller milestones or targets that you can work towards achieving. By setting specific goals, you create a roadmap for your progress and can track how far you’ve come. Regularly monitor your performance, celebrate small victories, and reflect on areas where you may need to focus more attention. Goal-setting helps you stay motivated, maintain direction, and overcome the illusion of skill acquisition by grounding your efforts in tangible outcomes.

One more thing…

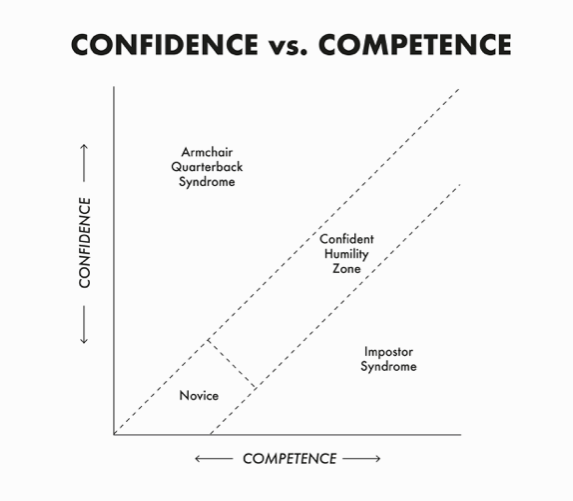

Although learning can occur from observing others perform something, the observer’s confidence in their own ability to perform the skill can also be a determining factor. This can cause the false increment of their ability to perform the skill compared to their actual ability. This illusion of motor competence – i.e., “Overconfidence” arises because the learner doesn’t get access to sensory feedback about their own performance.

So the next time you see a video with someone performing or doing something, ask yourself – “Can I really really do it?”.