The Diagnosis Pitfall

A woman – visibly in panic and grief – runs into the emergency room with her two years old daughter, who was experiencing severe stomach pains.

Normally, the ER (Emergency Room) doctor & the team would have started running tests for diagnostics. However, in this particular case, the ER doctors shifted their attention from the two-year old daughter to the mother, because the mother appeared to be overly concerned and seemed like a parent who would overreact. The doctors sent the mother-daughter home, dismissing any signs of impending severe dangers.

The woman returned the next day. While the ER doctors know how vital it is to carefully listen to the parents while treating infants, the doctors were now even more justified that the woman was overreacting, and labeled her as “hypochondriac”. Once again, the ER doctors sent them home, without proper tests and diagnosis.

The third day – the woman is back at the hospital with her daughter. It was only when the toddler lost consciousness, the doctors realized something was terribly wrong; but by then, it was already too late to save the precious life of the two-year old.

The moment the ER doctors labeled the mother “hypochondriac”, they fell into this pitfall of “Diagnosis Pitfall”, or “Diagnosis Bias”.

(Story adapted from Ori & Rom Brafman’s “Sway: The Irresistible Pull of Irrational Behavior”)

—

How can skilled, educated, and experienced doctors & physicians make such a disturbing decision? They go through years of rigorous training and intense practises because they’re responsible of saving someone’s life. But is it possible that even these knowledgeable doctors & physicians fall into the diagnosis pitfall?

Turns out, they can.

They’re humans after all. And our reliance on our cognitive process is vulnerable to biases, which makes treatment and diagnosis errors more likely than we think.

—

The journal article from Jill G Klein (associate professor of Marketing at INSEAD) published in the British Medical Journal (BMJ) explains about the five pitfalls in decision making about diagnosing and prescribing. The five common pitfalls are – i) Representative Heuristic, ii) Availability Heuristic, iii) Overconfidence, iv) Confirmation Bias, and v) Illusory Correlation.

“Studies based on both simulated cases and questionnaires show that doctors are susceptible to decision making biases, including insensitivity to known probabilities, overconfidence, a failure to consider other options, the attraction effect, and the availability heuristic. The good news is that training in these dangers can reduce the probability of flawed medical decision making.“

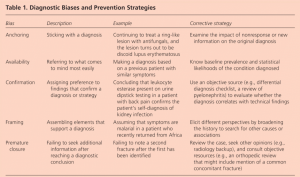

Caroline Wellbery, MD from Georgetown University School of Medicine, Washington, District of Columbia explains in her paper about the diagnostic bias and prevention strategies.

For a list and explanation about 50 various cognitive and affective biases in medicine, click here.

The Diagnosis Pitfall : How do you fall in?

In the above story, the doctors fell into the diagnosis pitfall in the moment they labeled the patient as “hypochondriac”.

When we label a person or situation, we put blinders to all evidence that contradicts our diagnosis. The “experts” at times are blinded by their past experiences, and could be fixated on the new event being the same as their past events. This happens to all of us. When we tend to selectively focus only on a part of the event that triggers our inner advice monster, we succumb into this trap of diagnosis pitfall. When we listen to someone sharing their story, and a part of it resembles our past event, we quickly prescribe them what had worked for us without realizing their situation might be completely new.

“When we tend to selectively focus only on a part of the event that triggers our inner advice monster, we succumb into this trap of diagnosis pitfall.”

There are usually three parts in falling prey to this biasness, viz. i) selective focus, ii) awakening inner advice monster, and iii) putting blinders to evidences that contradicts our diagnosis. Selective focus is when we tend to pick up only the selected event that resembles our past experiences and then zone-out the rest. Then, we subconsciously awaken our inner advice monster to prescribe what worked for us in the past, and finally, we do not look up enough evidences and factors that can contradict the advice we are about to prescribe.

The Diagnosis Pitfall : How do you get out?

To overcome this diagnosis, we need to understand how we get in first. Once we understand the “getting in” part, we can become aware of this dangerous pitfall, and the cost of this pitfall could be catastrophic. Being aware of our cognitive biases is the step one of overcoming any biases.

Second, understanding the three steps of falling prey to the diagnosis pitfall is essential. The answer to “getting out” of this pitfall is hidden in the route to “getting in” this pitfall. To overcome selective focus, we need conscious and empathic listening. When someone is sharing their situation, it’s not only the words that we should be paying attention to. Empathic listening is about letting the speaker know that we are genuinely interested in listening to them, we understand their problem as well as how they feel about it.

Taming the inner advice monster could be hard, but not impossible at all. To tame our advice monster, what we want to do is replace our advice-giving habit with a new habit: Staying curious. It’s as simple — and as difficult — as that.

Only when we have listened empathetically and not awakened our inner advice monster in between, we can then finally look for prescriptions. However, we should also be aware to look out for evidences that contradicts our prescriptions. In addition to vouching for “how this advice could work for you because it worked for me”, we should also seek to answer “how this advice could not work for you”.

Each person and each situation is different. Therefore, practicing a beginner’s mindset – or “shoshin” – could be crucial to overcome this pitfall. As Dr. Tracy Ochester (author of ‘Attitudes of Mindfulness: Beginner’s Mind’) puts it, “when we adopt the mind of a beginner, we endeavor to look at things as if for the first time, free from the influence of the past or speculation about the future. We open ourselves to what is here now, rather than constructing stories about what we think is here”.

Read Next: Don’t think outside the box