The famous Spartan warriors had a credo for their war – “Sweat more in practice, bleed less in war“. Practice is probably the greatest thing humans can do, yet people ridicule it.

For every new thing or an idea that has been brought into the world, people have laughed at it, criticized it, and ridiculed it at the beginning. As the famous quote wrongly misattributed to Mahatma Gandhi goes, “First they ignore you, then they laugh at you, then they fight you, then you win.“

This quote is a summary of Nichoas Klein, an American labor union advocate and attorney, who gave a speech to the Clothing Workers in May 1919, where he said the following:

[…] And my friends, in this story you have a history of this entire movement. First they ignore you. Then they ridicule you. And then they attack you and want to burn you. And then they build monuments to you. And that is what is going to happen to the Amalgamated Clothing Workers of America. And I say, courage to the strikers, and courage to the delegates, because great times are coming, stressful days are here, and I hope your hearts will be strong, and I hope you will be one hundred per cent union when it comes!

This ridiculing of new thoughts and ideas goes way back in our human civilization. Back when we humans didn’t know earth revolves around the sun, the accepted norm was a geocentric approach – which states that our Earth is at the center of the Universe. Even great philosopher and thinker like Aristotle was in favor of geocentric approach.

When Aristarchus of Samos presented the first known heliocentric approach that placed the Sun at the center of the known universe, with the Earth revolving around the Sun once a year and rotating about its axis once a day, it was met with rejections in favor of geocentric theories of Aristotle and Ptolemy.

In the 16th century, Nicolaus Copernicus, a Polish mathematician and astronomer, formulated a model fo the Universe that placed the Sun rather than Earth at its center. However, he was not certain if he wanted to publish his book containing this fact because of his concerns about possible astronomical and philosophical objections and/or religious objections.

However, in the 17th century, Galileo Galilei presented supporting observations about Copernican heliocentrism (Earth rotating daily and revolving around the Sun) using a telescope. This was – again – met with opposition from within the Catholic Church. The Roman Inquisition concluded that heliocentrism was foolish, absurd, and heretical since it contradicted Holy Scripture. Later on, Galileo was found “vehemently suspect of heresy” by the Inquisition, and thus had to spend the rest of his life under house arrest.

Long before the geocentric theories of Aristotle, the great philosopher Socrates was also executed by forced suicide by poisoning, because he was accused of corrupting the youth and failing to acknowledge the city’s official gods. In 399 BC, his trial lasted a day, and was sentenced to death for his radical thoughts and ideas.

In a world full of ridiculing, why should we practice?

Let us first go back to the time, when ancient humans discovered fire.

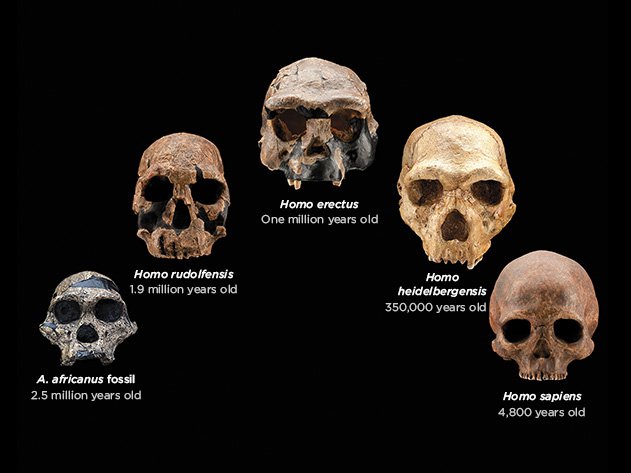

Although the direct evidence is scarce, claims for the earliest definitive evidence of control of fire by a member of Homo ranges from 1.7 to 2.0 million years ago. Evidence for the “microscopic traces of wood ash” as controlled use of fire by Homo-erectus, beginning some 1,000,000 years ago, has wide scholarly support [a].

In a review for the Royal Society Philosophical Transactions B, J.A.J. Gowlett hypothesizes that hominins took advantage of natural wildfires for foraging. It is difficult to follow the development of human control over fire because of what Gowlett calls its “disappearing act.” Fire isn’t as well preserved in the archeological record as, say, middens or flint tools. And progress was incremental, with fire control being learned in different places at different times. Certain archeological sites have proffered a bounty of stone tools, suggesting long-term quartering. Such occupancy could mean hominins learned to at least maintain fire as far back as 2.5 million years ago. But direct evidence is scarce [b].

So what happened after we discovered fire?

The cooking hypothesis, proposed by Richard Wrangham, Ruth B. Moore, Professor of Biological Anthropology at Harvard, claims that fire allowed us to cook our food – making cooked meats easier to chew and digest; and as a result, our bodies could extract more nutrients form the same amount of meat. Wrangham argues that the ability to create cooked foods shaped the brains and bodies of our Homo ancestors. Larger brains allowed us to process more information, create more dynamic social groups, and adjust to unfamiliar habitats. All of which benefited us evolutionarily [b].

Cooking can be thought of as “pre-digesting.” Because we’ve already broken down much of the food by cooking, the calorie absorption process becomes more efficient than if the food had been raw, and requires that we put in a significant amount of energy to just digest. The use of fire to prepare food paved the way for the evolution of organisms that could support significantly larger brains [c].

Thus, we are where we are now because of practice.

How?

Imagine a scenario – one of the ancient homo species discovered fire and showed it to his close group. He may have been ridiculed, laughed at, or may even have been accused of creating something dangerous and potentially destroying weapon! But had that one homo species given up, and left the practice to discover fire and educate more species, we would probably not have evolved so much as we have now.

Practice enabled humans to discover fire. With fire, humans were able to consume cooked foods. This allowed our body and brain to gain valuable nutrients required for our continuous development. Darwin himself considered language and fire as the two most significant achievements of humanity [d].

So how do you build habit of practice?

Step 1: Shut up and show up.

As James Clear, author of Atomic Habits, say – shut up and show up. Showing up is the first step towards practice and building long term habits. No matter what, show up. Take that first step.

Step 2: Know the environment.

Our environment also plays a vital role in building any habit of practice. If the people around us talk about football all the time, we are bound to watch football – because as humans, we are wired to comply with social groups. If people around us are appreciative and supportive enough, we tend to take the step we never thought we could take. The safety net from our environment really helps in taking new strides. If people around us aren’t supportive, maybe we need to change our environment around us.

Step 3: Use visual cues.

Small wins are massive motivators, but we rarely recognize them. Having a small win, and assigning a visual cue to it is important in any practice. Visual stimulus is important. It makes us stick with good habits. The visual cues act as a reward system for us to continue practicing. A small ‘tick’ on our calendar or marking done in our to-do list are all examples of visual cues working with our brain to reinforce our habit of practicing.

—

A constant reminder for myself to practice comes from my name itself – Prayas, meaning ‘try’. Let’s give it a try. Let’s take the first step.

And let’s keep practicing.