“Too many cooks spoil the broth” — this popular idiom implies that when too many people work together or are involved in an activity, the final outcome or result becomes inferior.

While we all agree to the idioms with our versions of experiences, a popular management term “synergy” comes into mind. On a flipped perspective of the idiom, shouldn’t multiple cooks be rather reinforcing the broth with their own camaraderie and united strength than spoiling it?

This proverbial expression metaphorically denotes employing excess resources causes inefficiency. On a more literal term, too many cooks might not always spoil the broth. It is having multiple inputs from too many people that derails the progress. Contrary to the belief, there can be multiple number of people and less number of inputs. Sounds superficial and counterintuitive, but it is not impossible to achieve.

The Earned Dogmatism Effect: Culprit for the Spoiled Broth

“We don’t know everything, and we probably never will.”

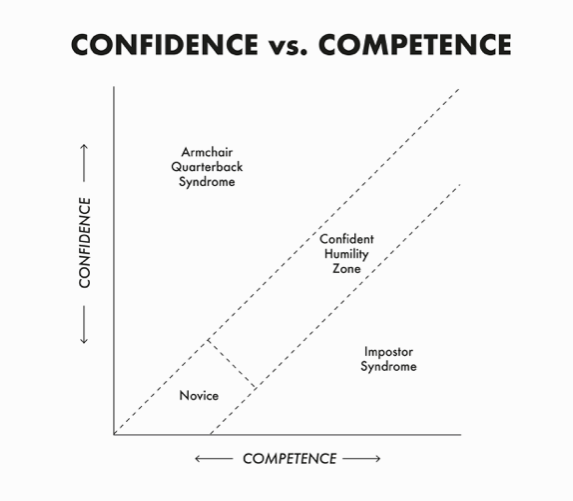

This sentence sums up the antidote to the earned dogmatism effect, which explains that as we start becoming more experienced and knowledgeable – and thus, move from amateur to expert, we start becoming more close-minded and adopt a relatively dogmatic orientation – inclined to lay down certain beliefs as incontrovertibly true. Little do we know, multiple truths exist.

Read in detail about ‘The Earned Dogmatism Effect’ here.

When the cooks start believing that their way is the “ultimate right” way, the broth gets spoiled. If the cooks (or anyone in general) become more self-aware of their own dogmas and its impact on the bigger picture (i.e., the spoiled broth), they can help prevent this accident. Of course it is against the common human nature to not add recommendations in such quandary. But this should not be seen as a “sacrifice” because one does not necessarily have to put forward their ideas and recommendations all the time.

How to Save the Broth?

Here are a few steps (out of many) to help us save the broth and move towards achieving ‘synergic’ results.

1. Self Awareness

Checking in with yourself always helps. As the popular saying mentions, “the only way out is in“. It becomes important to understand how our thoughts, emotions, and actions are ever evolving and changing as we learn, and grow more with education and experience in life. The more we know, the more likely we are to fall into the diagnosis pitfall. The diagnosis pitfall notes that the “experts” at times are blinded by their past experiences, and could be fixated on the new event being the same as their past events. When we tend to selectively focus only on a part of the event that triggers our inner advice monster, we succumb into this trap of diagnosis pitfall.

Read in detail about ‘The Diagnosis Pitfall” here.

As credible and knowledgeable experts, it becomes easy for us to advice people irrespective of their need for the guidance. Taming our inner advice monster is essential, and so it understanding that advice giving is not the problem.

Advice giving becomes problematic when i) we fail to understand the real depth of the challenge or the problem, ii) we think our advice is amazing when it might not be (Knock, knock: The Dunning-Kruger Effect), and iii) most frustratingly we cut away the other person’s sense of confidence and autonomy by trying to be a messiah or savior with our advices.

Self awareness helps us to check our biases within us, and realize that these cognitive biases can be problematic not just for us, but for the overall team and the outcome of the project/activity.

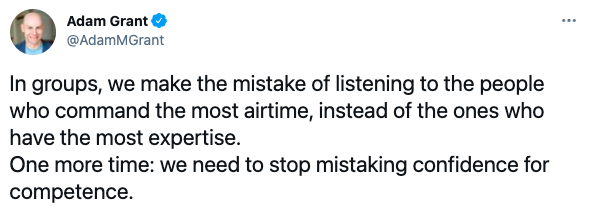

2. The golden pyramid of conscious and empathic listening

The golden trident of listening effectively comprises of three components – i) Understanding, ii) Humility, and iii) Curiosity.

Listening to someone should be more about understanding, and not about responding or reacting. And to make things clear, understanding does not mean agreement. We can develop this amazing ability to listen to someone say a complete opposing view without agreeing to them, but trying to understand where they are coming from.

The second component is about having the intellectual humility, since we do not have the knowledge of everything in the world. Even if we might have mastered cooking, we might not have full comprehension about all the dishes of the world. This humility allows us to listen rather than recommend more inputs to spoil the broth. Finally, the third component is about curiosity. Curiosity can be summed up with two words – asking questions.

Imagine you were about to clean the dishes voluntarily. Then someone comes in and then asks you to clean the dishes. You, now, might still do it but not as wholeheartedly as you would have done it before. Now imagine that instead of that someone ordering you to do it, they come up to you and simply asks, “what are you about to do?” Your probable response would be, “I’m about to do the dishes”. You might find the difference in your thoughts, emotions, and actions while doing the dishes now.

As human beings, being asked questions is a way to open up discussions and create platform to express ourselves. Asking questions implies that the other person is curious to listen, know, and understand about your views. Asking questions and staying curious in the conversation is more likely to push you to a listening zone. As the principle of reciprocity goes, when you listen to someone, you get listened to as well.

3. Imposed gets opposed.

Finally, when we try to impose our ideas and recommendations on others, we can expect it to be challenged, criticized, and even opposed.

Imagine your vegan friend pressing you hard to leave your juicy steak and turn into adopting a plant based diet. Imagine a religious priest avouching you to turn into following a certain religion, or trying hard to turn your atheist views to believing in god. Imagine someone with high inclination towards alternative medicine trying to influence and persuade you into following their methods. When you feel these things being imposed on you, you won’t budge no matter how much of logical statements they make, or how much evidences they present to you. They simply come across as “logic bullies“.

Any idea or change that is imposed will largely get opposed. In order to save the broth, we need to remain mindful that we are not imposing our inputs and recommendations to others. Understanding this simple rule will help us to easily get things done through our teams and groups.

Even the recommendations mentioned here in this article are not imposed; people are free to practice their own will. Just don’t impose it to others.